Roadmaps are a pretty popular topic whenever Product Managers congregate — whether that’s online or at events like ProductCamp. It’s also one of the things that new Product Managers or Product Managers moving into a new role in an organization often struggle with. It doesn’t help matters that different companies, different execs, and even different product managers can often have entirely different opinions about what a roadmap is, what it looks like, and what it’s supposed to be used for.

But the Clever PM has never been one to shy away from a challenge or from a controversial issue — so let’s take a closer look at exactly what product roadmaps are, why they’re important, and what you should probably include (or exclude!) from yours.

What a Product Roadmap isn’t…

First, let’s get rid of some of the common misconceptions about what a Product Roadmap is. A product roadmap is not…

- A crutch for Sales to use when they can’t convince customers of the value proposition or communicate the product as a solution to present problems.

- A magical prognostication of the future that predicts exactly where the market will be in 12-24 months.

- A project plan that specifies resources, specific project scope, and time-boxed commitments to deliver.

- A tactical tool that is constantly updated and changed on the whims of the execs and/or the Product Manager.

A product roadmap is:

- A tool used internally to ensure that people understand the strategic direction of the company and how that translates into planned thematic areas of improvement.

- A tool modified for use externally to provide key customers and prospects with a feeling of satisfaction that your company has an understanding of the direction of the market and is investing in the future of the product.

- A strategic picture of the intended future of the product, with increasing levels of uncertainty as the time horizon extends beyond the present.

- A reflection of the current understanding of the market, the product, the users, and the company that is updated only when needed or when changes occur that require a response.

Whenever someone asks me about roadmaps, I tell them that they need to figure out three things before even considering what to put down on paper or how to do it: (1) Who is your audience, (2) What is the purpose of the roadmap, and (3) How much detail do you really need in the document. If you can answer these three questions, putting together an actual roadmap is a snap.

Who is the Audience?

This is perhaps the single most important question of them all, as it is with any communication tool. In order to know what your roadmap should be, you need to know who is going to be reviewing it. Is the roadmap intended for external communications or internal communications? Is it intended to provide potential investors a view into a possible future for the company, or is intended to show prospects and customers the things that you’ve both promised and achieved? is it something that you’re going to review with the company as a whole at a lunch & learn, or is it strictly for the executive team’s review and approval?

You’d never consider giving a speech without knowing who’s in attendance and what their interests are. And you’d never think to prepare a marketing campaign without knowing your audience. So why do we think that there’s some generic, global answer to creating a roadmap — there isn’t. Who’s going to be reviewing the work is always the most important question in how you construct the content, how you display the information, and how, when, and where you present and discuss the artifact. Not knowing your audience guarantees that you won’t create an effective roadmap.

What is the Purpose?

Once you know your audience, you need to decide what it is that you want to achieve with your roadmap. In the classic old days of Waterfall development, the “roadmap” was practically a Bible carried around by salespeople who sold things that didn’t exist yet, rather than selling the value of the product. The waterfall roadmap was a “vision” of an optimistic future, in which what we know now will maintain and be predictable for 9, 12, or even 24 months. In this day and age, everyone should be able to see how ridiculous that is.

But, the roadmap is still used as a crutch by sales. And it’s still used to make promises that the Product team has to follow up on. And, usually, that’s because the document itself didn’t have a specific purpose in mind when it was created — which gives everyone in your organization a license to use it for whatever purpose they want. We as Product Managers need to own that purpose, and to make it clear not just in the communications surrounding the document, but in the document itself.

If you want to make sure that your roadmap reflects the ambiguity and uncertainty that’s inherent in planning for the future, do so — within the document. Know what you want the document to say, how you want the document to be used, and ensure that the document reflects that purpose.

How Much Detail is Needed?

Which inevitably leads us to the question of how much detail is needed. Sales will always say that they need to know a specific time for a specific feature, so that they can reassure clients that you’re moving forward and delivering what they want. The CEO is going to always say that he needs a firmly-committed roadmap to make the investors happy and shows how visionary he (or she) is. Each and every team is going to have a different reason for wanting the roadmap, and each of those reasons is going to require an entirely different level of detail.

And I’m here to tell you that you can (kind of) satisfy everyone, by tailoring the detail to the certainty that you can have about what’s going on. The secret is to have a roadmap that’s tightly-committed in the short-term, loosely-committed in the near-term, and visionary in the long term.

For example:

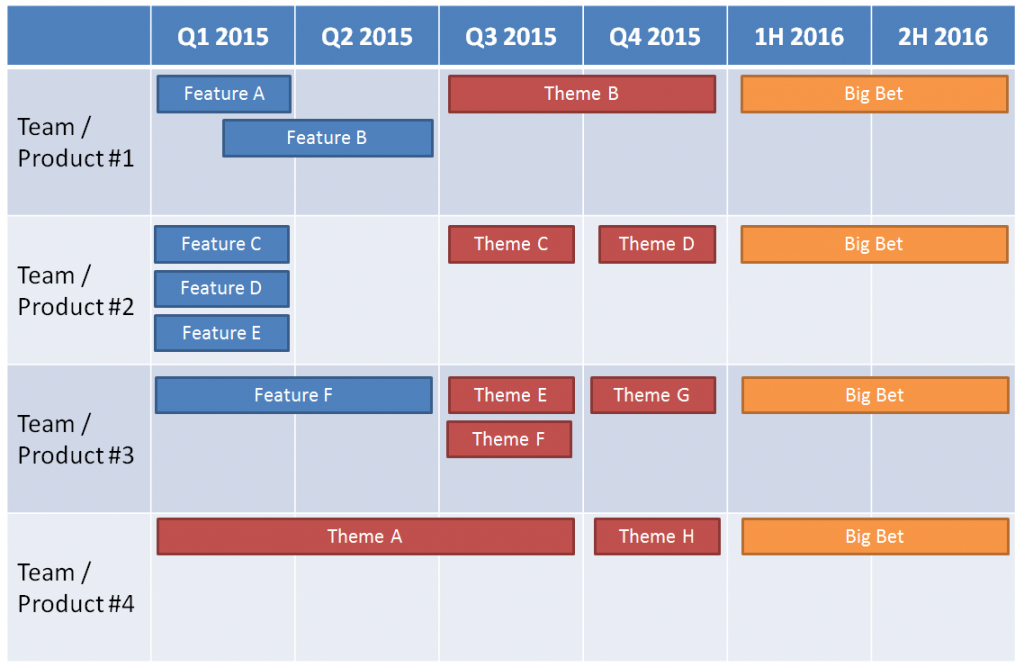

- For the next three months, you probably have a good idea of what features are going to be completed and/or what’s got a very good chance to get started and hopefully finished. These specific features should be called out in that time-frame.

- From thee to six (or maybe nine) months, you should have a prioritized backlog that you can look at to determine what are the likely thematic areas in which you’ll focus your efforts. Not features, but the next level up (think Epics or Themes) – those general areas that provide insight into the plan, but which allow for feature flexibility. “UX Enhancements”, “Scalability Improvements”, “Stronger Integrations”, “New Markets” – things like that, which show that you have a plan, but that the plan itself is flexible.

- Outside of this, everything is a total guess (unless you work in a very small number of markets where things are planned out in 24-month specific strategies). So buy into that – what are your “big bet” guesses as to where the market is going to be, and who you’ll be designing your product for? Put these in as large, high-level placeholders that cover large amounts of time with very little specificity.

In short, as your uncertainty about what’s actually going to be built grows, the level of detail that you provide and the specificity with which you provide it decreases dramatically.

Put it All Together and What Have You Got?

Bippity-boppity-boo, of course!

But no, there’s no magic here, no fairy dust needed. Just a basic comprehension of who it is you’re making the roadmap for, what the purpose is that you’re targeting, and what level of detail you’re shooting for.

As for what the final product might look like, here’s an example that I’ve put together from prior work, genericized for your own enjoyment.