Over the course of my career, I’ve had the chance to work with a wide variety of tools and methods to document how something should work, what user goals are, what the workflow should be, and generally how a user gets from point A to point B and beyond. Throughout all that time, I’ve noticed a definite pattern in when, how, and where you get the most valuable and actionable feedback. The key is to track the feedback that you get from your stakeholders along a spectrum from ideation and paper documentation, all the way through to delivery, and figure out at which point those groups provide the best, most actionable feedback.

Tracking to a Feedback Spectrum

Unfortunately, there’s no one, clear answer to where along this spectrum you should focus, because if you engage a stakeholder too early, and their understanding isn’t as strong as it could be, you might wind up introducing more randomization than you intend, since their decisions will be based on an incomplete view of what you’re trying to achieve. At the same token, if you engage too late, you might be incurring significant cost in responding to their feedback.

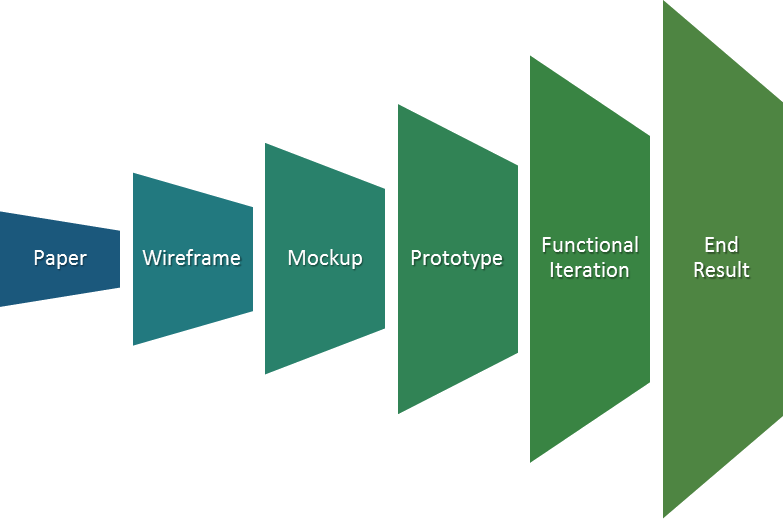

Here’s an example of the spectrum I’d use as an example – as you move from paper to your end result, the clarity of vision and execution grows, but so does the cost of responding to any feedback!

As your work becomes better defined, understanding grows, but so does the cost of responding…

Because your stakeholders will vary in regard to where they land on this spectrum, it’s absolutely imperative that you figure out which stakeholders provider higher-quality feedback early in the process, and which provide the higher-quality feedback later in the process. This allows you to stratify your approach to feedback and review, and ensure that you know when feedback is likely to be actionable and reliable, and when it may change in the future. While you may still review with everyone at each of these stages, understanding just how much action to take on any feedback that you receive will significantly lower the burden of rework and randomization as you move forward.

Avoiding the “Head-Nodding” Syndrome

We’ve all been there – early on, we review our plans with stakeholders, walk through the wireframes, maybe even a mockup, and they all say, “Yes! That looks great!” Then we get to something that actually works, and they try it out and become frustrated and confused — even though the work done exactly matches the work that you previously reviewed. You get frustrated, your stakeholders feel cheated, and the whole project goes up in flames — flames that you, as the designated firefighter, get to now put out.

The root cause of this explosion is a lack of comprehension on the part of your stakeholders when the original review was done; they simply lacked the vision, the understanding, or even the capacity to take the next steps in their mind to what the product would actually be. They may have had unstated assumptions, they may have projected their own vision onto the future, or they may simply have changed their minds in the interim — thinking that there’s always ample time to change the outcome.

What we should learn from this is that earlier is not always better when it comes to review and feedback. Review at the proper time in the process is what you’re aiming for. Certainly, you want that proper time to be as early as reasonably possible — but the risks of reviewing too early are just as dangerous as the risk of reviewing your product too late. It’s the nature of the problems caused by an early v. late review that are different.

The moral: figure out the best time to review with your stakeholders, and focus your efforts on feedback that you gain in that sweet spot.